A few weeks ago I was introduced to Jenna Laib‘s game “Number Boxes” and was very interested in using it as a dynamic game to help students learn a variety of new content — Jenna’s blog explaining the game can be found here: “One of My Favorite Games: Number Boxes“.

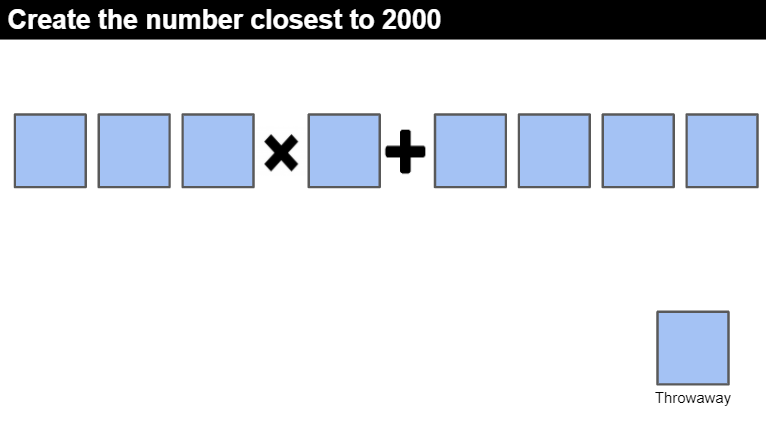

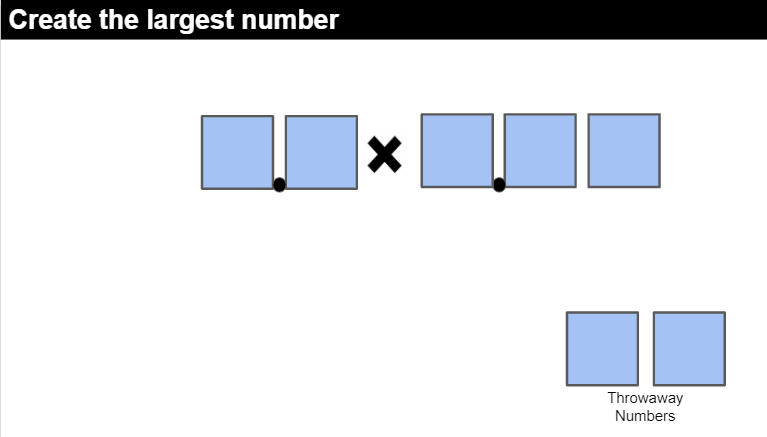

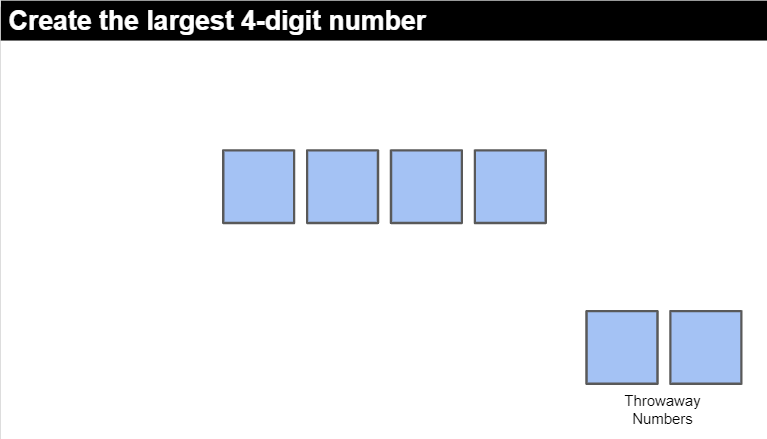

Basically the game involves students rolling dice (or spinning a spinner / drawing a card) to generate a random number and placing that number in one of their empty number boxes one-at-a-time. The game can progress in a variety of ways:

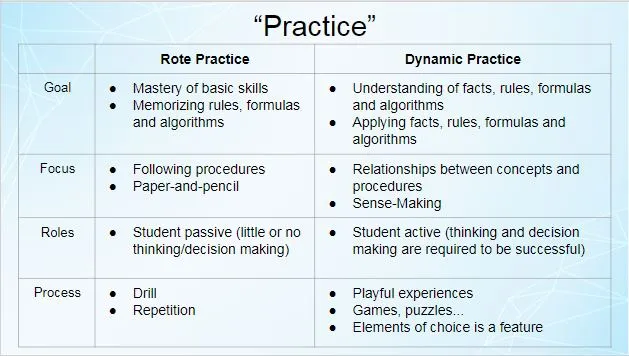

As you can see, the game is quite adaptive to the sizes of numbers and concepts your students are comfortable with. As students roll/spin/draw a number, they have to place it on the board. What makes this tricky is not knowing what future numbers will be. In the board above, you can see that there is also a “Throwaway” box that students can use if they do not like one of the numbers rolled/spun/drawn. This game is an excellent example of a “Dynamic Game” or “Dynamic Practice” as students are following the ideals on the right side of the chart below:

Blow is a gallery of some possible adaptations of this game or linked here is a slideshow

Metric Conversions

I however, wanted to use Jenna’s game to help students practice a concept they often have difficulty with – Metric Conversions. Once students have had many opportunities to estimate and measure various distances, capacities, and masses, they should be able to start making connections between all of the units. I suggest a good balance between using problems that help students make sense of the relationships between the units, and opportunities to practice conversions on their own. However, instead of randomly generated worksheets or other rote practice, I think Jenna’s game could work perfectly. Take a look at some examples:

Reflection

It is important to offer tasks that allow students to make choices and decisions like the ones offered in this game. Learning needs to be more than handing out assignments, and collecting work… Learning takes time! Students need more time to explore, see what works, have peers challenge each others’ thinking, make important connections… Hopefully you can see these opportunities in this task.

Final Thoughts:

- If you play one of these games, or your own version, will you first offer a simplified version so your students get familiar with the game, or will you dive into the content you want to teach?

- Would you prefer your students to play this game as a class or with a group, a partner, or independently?

- How will you build in conversations with students so they discuss which numbers they think should be the highest / lowest numbers? How will you offer time for these strategic discussions?

- Should we adapt these to continually offer more challenge and deeper learning, or offer more opportunities to play the same game board? How will we know when to adapt and change?

- What does “practice” look like in your classroom? Does it involve thinking or decisions? Would it be more engaging for your students to make practice involve more thinking?

- How does this game relate to the topic of “engagement”? Is engagement about making tasks more fun or about making tasks require more thought? Which view of engagement do you and your students subscribe to?

- How have your students experienced measurement concepts like these? Are they learning procedural rules or are they thinking about the actual sizes of numbers / sizes of the units involved?

- As the teacher, what will you be doing when students are playing? How might listening to student thinking help you learn more about your students? (See: Noticing and Wondering: A powerful tool for assessment)

I’d love to continue the conversation about “practicing” mathematics. Leave a comment here or on Twitter @MarkChubb3