Many teachers are comfortable allowing their students to read for pleasure at school and encourage reading at home for pleasure too. Writing is often seen as a creative activity. Our society appreciates Literacy as having both creative and purposeful aspects. Yet mathematics as a source of enjoyment or creativity is often not considered by many.

I want you to reflect on your own thinking here. How important do you see creativity in mathematics? What does creativity in mathematics even mean to you?

Marian Small might explain the notion of creativity in mathematics best. Take a look:

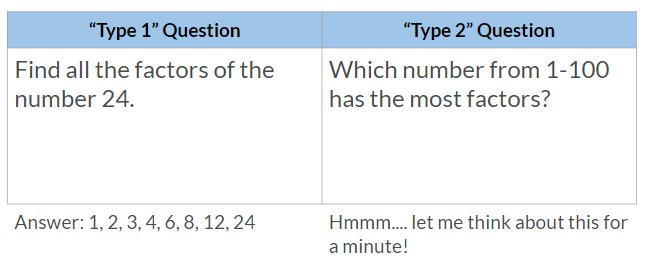

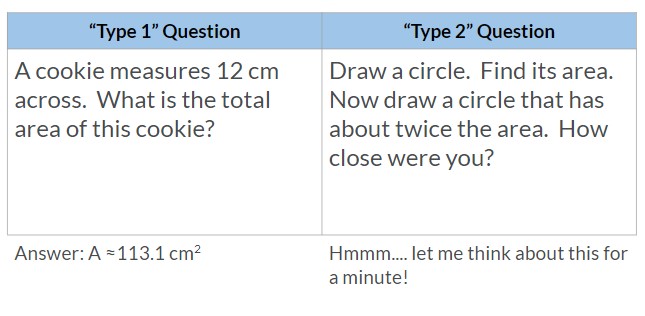

Type 1 and Type 2 Questions

Several years ago, Marian Small tried to help us as math teachers see what it means to think and be creative in mathematics by sharing 2 different ways for our students to experience the same content. She called them “type 1” and “type 2” questions.

Type 1 problems typically ask students to give us the answer. There might be several different strategies used… There might be many steps or parts to the problem. Pretty much every Textbook problem would fit under Type 1. Every standardized test question would fit here. Many “problem solving” type questions might fit here too.

Type 2 problems are a little tricky to define here. They aren’t necessarily more difficult, they don’t need a context, nor do they need to have more steps. A Type 2 problem asks students to get to relationships about the concepts involved. Essentially, Type 2 problems are about asking something where students could have plenty of possible answers (open ended). Again, here is Marian Small describing some examples:

Examples of Type 1 & 2 Questions

Notice that a type 2 problem is more than just open, it encourages you to keep thinking and try other possibilities! The constraints are part of what makes this a “type 2” problem! The creativity and interest comes from trying to reach your goal!

Where do you look for “Type 2” Problems?

If you haven’t seen it before, the website called OpenMiddle.com is a great source of Type 2 problems. Each involve students being creative to solve a potential problem AND start to notice mathematical relationships.

Remember, mathematically interesting problems (Type 2 problems) are interesting because of the mathematical connections, the relationships involved, the deepening of learning that occurs, not just a fancy context.

Questions to Reflect on:

- When do you include creativity in your math class? All the time? Daily? Toward the beginning of a unit? The end? What does this say about your program? (See A Few Simple Beliefs)

- If you find it difficult to create these types of questions, where do you look? Marian Small is a great start, but there are many places!

- How might “Type 2” problems like these offer your students practice for the skills they have been learning? (See purposeful practice)

- What is the current balance of q]Type 1 and Type 2 problems in your class? Are your students spending more time calculating, or deciding on which calculations are important? What balance would you like?

- How might problems like these help you meet the varied needs within a mixed ability classroom?

- If students start to understand how to solve type 2 problems, would you consider asking your students to make up their own problems? (Ideas for making your own problems here).

- How do these problems help your students build their mathematical intuitions? (See ideas here)

- Would you want students to work alone, in pairs, in groups? Why?

- If you have struggled with developing rich discussions in your class, how might these types of problems help you bring a need for discussions? How might this change class conversations afterward?

- How will you consolidate the learning afterward? (See Never Skip the Closing of the Lesson)

- As the teacher, what will you be doing when students are being creative? How might listening to student thinking help you learn more about your students? (See: Noticing and Wondering: A powerful tool for assessment)

I’d love to continue the conversation about creativity in mathematics. Leave a comment here or on Twitter @MarkChubb3